Putting a Gleam in the Eye

It's 6:42 p.m. in the control room at the CBS Broadcast Center on New York’s West Side, halfway through the CBS Evening News With Scott Pelley. The booth adjacent to the set is about half-full and in the state of controlled chaos that is a live broadcast. The female executive producer and three male senior producers, most of whom are 20-plus-year veterans of CBS News, are seated in front of monitors in one row, wearing headsets, barking cues to cut this segment or stretch that one. The production secretary runs pages of the updated script up to the director in the front row as they stream, almost continuously, out of a printer behind her.

On one of the many monitors hanging from the control room’s ceiling, NBC Nightly News’ Brian Williams teases an upcoming segment about the singer Sheryl Crow. The same Crow story was already mentioned in the headlines on ABC World News on an adjacent monitor. On the screen up front showing the CBS broadcast, correspondent Elizabeth Palmer, reporting from Damascus, has just wrapped a piece on Syria.

“Oh, they’re both doing Sheryl Crow,” notes Evening News executive producer Pat Shevlin during the commercial break, keeping one eye on the rundown and one on the competition.

“That was never going to happen,” says a senior producer seated to Shevlin’s left, offering a reminder that celebrity updates—a mainstay of so many quote-unquote news programs— don’t fit into the new CBS Evening News. And that is firmly by design.

It is June 6, the one-year anniversary of Scott Pelley taking over as anchor and managing editor of the CBS Evening News. And while Pelley, who calls himself “America’s least-experienced anchorman,” may not yet feel completely comfortable in the anchor chair, he is confident with where he wants to take the newscast and how he’s going to catch ABC for second place.

CBS News has languished in third place for more than 20 years while the broadcast network has spent the better part of the last decade as the most-watched channel in primetime. The division’s Katie Couric experiment couldn’t live up to the hype, and countless reinventions of The Early Show did nothing to jump-start its ratings.

The exception is CBS’ 60 Minutes, which on many weeks of the season is still a top-10 show. So when CBS tapped the venerable newsmagazine’s executive producer, Jeff Fager, as chairman of the news division in February 2011, the direction from CBS CEO Leslie Moonves was simple: Make CBS News like 60 Minutes.

It’s a somewhat counterintuitive strategy when everyone else in network news is running in the other direction. Good Morning America has gone softer in the era of ABC News president Ben Sherwood— and it has snapping Today’s 16-year win streak to show for it, causing the NBC morning show to pull stunts of its own. Plus, the conventional wisdom says that hard news doesn’t work on TV—just look at CNN’s well-documented ratngs challenges.

But CBS is betting that Fager and his deputy, CBS News president David Rhodes, are the ones to pull it off, with an all-in strategy to remake the news division in the image of 60 Minutes, including plucking one of the program’s correspondents to helm the Evening News.

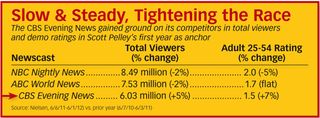

They are one year in, and the CBS Evening News is the only newscast whose ratings are up year-over-year, rising 7% in viewers 25-54. That nothing-to-lose strategy just might be working.

The Reluctant Anchor

Despite perennial speculation over the years that he was destined for the anchor chair, Pelley always insisted his place was solely at 60 Minutes, even telling B&C in a 2007 profile that while being anchor is “a tremendously important job, especially in times of crisis, at the end of the day, it is largely an office job.”

So what changed his mind? For one, his boss, Fager—whom Pelley calls “the author of my career”—was the one asking, and he saw the importance of providing leadership at the only network he has ever worked at or wanted to work at.

“I love this place. Given the opportunity to try and come in and make it better, make it what it was, was a very attractive thing to me,” Pelley says. “The reason Jeff Fager asked me to do this was not because he was looking for an anchorman. If you’re looking for an anchorman and you look at my resume, it’s not there; you don’t hire me. What he wanted me to do more than anything was to be the managing editor. He said, ‘Make it like 60 Minutes.’”

To observe Pelley as the broadcast is put together is to see just that. He is active in reading, writing and rewriting the stories (there’s no such thing as good writing, only good re-writing, he likes to say), and tweaking headlines. When he gives a note on a correspondent’s piece, it is usually about adding context to the story, explaining the larger implications of a regional story or adding balance with an opposing viewpoint.

Used to doing on-location stand-ups for his 60 Minutes pieces (and in his 14 years as a local TV producer/reporter in Texas before joining CBS News in 1989), Pelley has spent the last year learning to communicate with an audience from behind a desk. The first broadcast he ever anchored was the Evening News, and he says settling into the chair is “still a work in progress.” (That’s if you take his word for it; Pelley’s EP, Shevlin, says he’s a natural.)

“It’s a very artificial setting to be speaking to someone from,” Pelley says. “What a really good anchorman has to do is speak to the people in the darkness who are there and not let the machinery and artificiality get between the two of you. And I get that, and I think I know how to do it. I just don’t think I’m quite there yet.”

No Longer a Rookie

Today, like all days, Pelley has been online since 8 a.m., using the commute from Connecticut to email back and forth with producers while reading The Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Washington Post and National Journal on his MacBook Air in the car. He arrives at the office around 9:15 a.m. dressed in a blue suit, white dress shirt with cuff links and purple-blue tie. Everyone in the newsroom is dressed fairly formally, with male producers in shirts and ties and women in dresses or pantsuits.

His first stop is the editorial office known as the “fishbowl,” for its windowed wall facing the main newsroom. This is where Pelley spends the majority of his day with the program’s seven-person senior editorial staff, who fill a large circular table. Each spot has a computer, TV screen and phone, while three small TVs on each side of the room are constantly tuned to CNN, MSNBC and Fox News.

By the time Pelley arrives, the night’s broadcast already has a lead story—correspondent Dean Reynolds is working on getting a oneon- one with Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker, who survived a recall election the night before—and an end piece, in part two of Steve Hartman’s “On the Road” segment on the anniversary of D-Day which aired the night before.

At 9:45 a.m., it’s up to his office to refill his coffee—his third cup of the six or seven Pelley will consume in a steady stream throughout the day along with handfuls of cashews, which he stockpiles in bags in his desk.

Pelley’s second-" oor office overlooks the newsroom and is decorated classically, with an Oriental rug, dark wood furniture and leather sofa—a much different feel than the stark white office Couric kept. Pelley also added a small gym in a room to the side with a weight machine, treadmill and free weights for midday workouts to keep up his trim frame.

Above his desk hangs a large painting of a sailboat commissioned by his wife, Jane. Pelley is between boats right now, but used to sail often on Long Island Sound before he took up his current seven-day-a-week work schedule necessitated by his dual role helming the Evening News and as a 60 Minutes correspondent.

“There isn’t much time for sailing anymore, I’m afraid,” he says. “Which is too bad, because it really clears the mind. When the Evening News is No.1, I’ll start sailing some more.”

While Pelley may keep the monitors in the Evening News studio that used to show ABC and NBC off to avoid comparison to the competition, he still thinks about his place in the pecking order of network news.

“It bothers the hell out of me that we’ve been in third place for a very long time, more than 20 years,” Pelley says. “So that’s a great challenge. And I mean great in every sense of the word—it’s a large challenge and it’s a fun challenge.”

He notes that the Evening News has narrowed the gap with World News in the last year. Pelley plans to keep narrowing it by bringing in more of the 60 Minutes feel, like making the investigative reporting more aggressive and taking the broadcast on the road more often. “I would like to be able to tell you that we’ve overtaken ABC,” he says of his goal for next year. “I don’t know any reason why that isn’t possible.”

At 10 a.m., all of the CBS News broadcast staffers gather for the daily editorial meeting to go over the stories of the day, but Pelley hangs back in the fishbowl.

“I don’t like meetings; I’ve cut as many of them out as possible. I would argue in this day of email and IM, we already know what’s going on. Obviously,” he says, gesturing at the deserted room, “I’m in the minority.”

He uses the time alone to read Hartman’s D-Day piece, about a World War II widow who learns decades later that her husband, listed as missing in action, is considered a hero in a small French town. He tears up for the first of several times in the day.

“My daughter says I cry at sunsets,” he remarks.

The producers return from the editorial meeting around 10:25 a.m., and shortly afterwards, news breaks that the author Ray Bradbury has died. Pelley recalls reading all of his books in middle school. They debate if the story deserves an anchor track or a piece, and task someone to find footage from the last time CBS News profiled Bradbury.

“This is starting to get kind of crowded, this newscast,” Pelley says, noting that Bradbury’s death may have bumped from the lineup a planned piece on Pakistan cutting the U.S. supply line to Afghanistan. “The news of the day is starting to put pressure on the stories I really care about.”

A Double Life

At 10:45, Pelley is dodging traffic on 57th Street to get to the 60 Minutes offices, which occupy the ninth floor of the building across the street from the CBS Broadcast Center. The office is fairly empty—the newsmagazine is off-season—but Pelley greets all the staffers who are there by name.

Unlike the windowless Evening News space, which Pelley calls “very much like working in a submarine,” his office at 60 Minutes is bright with natural light and a view of the Hudson River.

He has come for an 11 a.m. meeting with Harry Radliffe, a 60 Minutes producer, with Bill Harwood, CBS News’ NASA consultant, on the phone, to discuss an email complaint Pelley received from Neil Armstrong—yes, that Neil Armstrong—late the night before. The former astronaut is upset with what he argues was a misrepresenting of his congressional testimony in a piece Pelley did on the SpaceX company. Armstrong claims he has been trying to reach 60 Minutes for months without success, which distresses Pelley.

After a 15-minute meeting, it is agreed that the reporting of the segment was solid, but Pelley still wants to publicly acknowledge Armstrong’s response, either on the Website or on-air, given his prominence. Pelly instructs the two others to draft a letter to Armstrong that he can review later that day.

Pelley then heads down the hall to another meeting, this time in a windowless edit room, with two other 60 Minutes producers (and a third on the phone from Washington, D.C.) to review footage from his recent trip to Togo, where he shot a story about a civilian hospital ship that performs surgeries on Africans who often come in with horrifically overgrown tumors. Pelley tears up for the second time.

Pelley’s day job means that stories involving travel have to be shot on the weekends, leaving him 36 hours for a piece that he may once have given five or six days. “What I miss more than anything are those big adventure stories that take a lot of time,” he admits.

If Pelley has had to give up some world traveling, he has gained the ability to pull double-duty, taping segments for 60 Minutes while covering breaking news on the road for the Evening News, as well as double exposure for his and other correspondents’ 60 stories, many of which air on the evening newscast—an unthinkable practice a year ago.

“There used to be a Chinese wall down the middle of that road,” he says, referring to the block of 57th Street that separates the offices. “Jeff put an end to that instantly by coming over here. That’s a great thing.”

Back at the Evening News, Pelley gathers the newsroom for lunch at 12:30 p.m. As a surprise, the Texas-bred Pelley has catered in Hill Country barbeque and bought CBS Evening News With Scott Pelley baseball caps for all the staff. On the back, the word “integrity” is positioned beneath the network’s famed Eye logo.

“I am immensely grateful for every sacrifice that you and your families have made,” he tells the staff in a brief speech. “So thank you, we’re on the way to No. 1, it’s demonstrable now.”

A few staffers come over to give him hugs and snap a few photos. Pelley’s assistant has taken some barbeque up to his office. But the anchor doesn’t eat it yet, instead donning his new cap and heading back to the ! shbowl to talk with his foreign news producer, scan news sites and work on his Bradbury obituary. He grabs a Greek yogurt from the fridge and mixes in the cashews.

At around 1:35 p.m., Pelley heads upstairs for a 50-minute workout, showers and changes into his clothes for the broadcast: black suit, blue shirt, blue striped tie. At 3 p.m., it’s time for the daily editorial meeting. About 25 Evening News staffers pack the fishbowl, where Shevlin goes over the night’s broadcast as of now. During the meeting, Pelley’s assistant sneaks in to hand him a message—he has missed a call from Moonves. Immediately after the meeting wraps, Pelley calls Moonves back, then delivers the CEO’s words of encouragement to the room. “He says he’s so proud of CBS News, that we’ve made him proud.” Pelley decides to send his boss a cap.

After pre-taping an intro for the Syria segment (Pelley uses two takes to get the toss right—“I’m just getting warmed up,” he says), it’s back to the fishbowl, where he reads emails, gives his head writer notes on headlines and tweaks the Bradbury obit. At 4:40, there’s yet more caffeine: His assistant brings him a venti Starbucks. By 4:45, correspondents have started filing reports and the busy jockeying for segment time begins, along with a clear increase in the energy of the room.

“This is when things start to pick up speed,” Pelley says.

At 5:30 p.m., Pelley is back in the studio to tape headlines and previews for some of the local affiliates. He keeps a laptop at the anchor desk so he can write between takes. Back in the fishbowl, Pelley and the producers make last-minute cuts to make their runtime and debate the final wording of lines, which will continue to be changed during the broadcast seconds before Pelley must say them.

The anchor is on-set for good at 6:15 p.m. to do a live hit with WBBM Chicago, where the local anchors congratulate Pelley on his one-year anniversary, the only such reference that will be made of the milestone on-air all day. Not one to miss an opportunity, Pelley works in a reference to the 30% ratings gains the Evening News has seen in the Chicago market, a seamless plug that receives kudos from the producers in the control room.

At 6:27 p.m., Pelley’s makeup has gotten its final touch-up. All the producers have finally assembled in the control room. The lineup’s runtime is only two seconds over. At 6:30 p.m., as the taped headlines begin to play, Pelley shares one last thought over his mic: “Everyone, welcome to our second year. Thank you, and good luck.”

A Year in Review

Back in the newsroom at 11 a.m. the next day, the staff of CBS News is again gathered, this time for a town hall meeting led by Fager and Rhodes, the first since the pair took over the news division early last year. All the staff of the Evening News is there, including Pelley, plus CBS This Morning coanchor Gayle King and VP of programming Chris Licht, among others.

The occasion is Pelley’s one-year anniversary, and Fager takes the opportunity to praise the program for rebuilding not in the image of its competitors, but itself. “There’s so much junk out there,” Fager says to the packed newsroom, calling out newscasts that follow audience research away from stories like Syria and other hard news, reinforcing the idea of putting together a broadcast at CBS News that viewers get something substantive out of.

“That’s a huge part of what we do,” Fager says. “If we were out to do something different, we wouldn’t be very good at it.”

E-mail comments to amorabito@nbmedia.com and follow her on Twitter: @andreamorabito

Broadcasting & Cable Newsletter

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below