LPTVs, FCC Square Off in Court

Attorneys for LPTV station owner Mako Communications and LPTV option owner FAB Telemedia told a federal court Thursday (May 5) that the FCC is trying to turn those stations' acknowledged secondary status when it comes to interference issues into a blanket license to displace them in the spectrum auction.

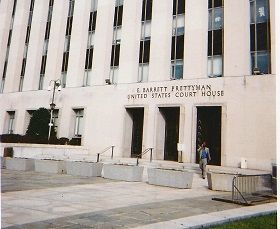

The LPTV attorneys squared off against the FCC in oral arguments--their related challenges were heard separately one after the other--in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

Hearing the appeal was a three-judge panel comprising Judges Thomas Griffith, Sri Srinivasan and David Sentelle.

Mako's arguments were mostly on substance, while FAB's counsel spent most of his time arguing for why it had standing to bring the court challenge--it owns options to buy LPTV's from Word of God Fellowship, rather than owning the stations themselves. Word of God, which also has auction eligible stations.

But both Mako and FAB argued that the FCC was violating the congressional directive in section b(5) of the spectrum auction legislation saying that "nothing in the incentive auction 'alter[s] the spectrum usage rights," of LPTV stations.

Mako and FAB argue that the FCC did just that in requiring LPTV's to relinquish their spectrum if there is no place to repack them.

FCC Attorney Jacob Lewis said that b(5) essentially prevented the FCC from being able to displace LPTV's without respect to whether or not they would interfere with full-power or Class A or unlicensed wireless spectrum users, given the new repack authority the FCC was also getting in the statute.

Broadcasting & Cable Newsletter

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

He said without b(5) the FCC could have used its broad authority to simply displace any LPTV, whether or not it interfered with any other station or license holder. The FCC does have broad discretion to reclaim licenses if it deems that is in the public interest, something that concerned full powers as well if that meant they might someday have to give up spectrum without compensation if the FCC did not get enough participation in this auction.

Lewis likened LTPV's regulatory status to that of a passenger flying standby who would not get to fly if all the seats were taken.

FAB's attorney countered that they were already on the plane--they are a licensed service--and b(5) means the FCC can't just throw them off because it wants to.

The flying metaphor kept taking wing, though Sentelle suggested metaphors didn't always work. Lewis suggested that the fact that the FCC band plan left the fewest remaining channels was like waiting for a 747, then having it replaced by a 737, there would be fewer standby seats, i.e. channels available for LPTV.

Judge Srinivasan probed the issue of whether b(5) wasn't simply a way to prevent the FCC from indiscriminately preventing the FCC from booting LPTV's rather than protecting admittedly secondary LPTV's from displacement.

Mako maintained that while the statute made clear that LPTV coverage areas and population reach would not be protected in the repack per statute, as they were for full powers and Class A's, the FCC was trying to expand that to mean LPTV's had essentially no rights, including to the spectrum they were licensed to hold.

Srinivasan said it sounded like Mako was saying b(5) was an additional protection, but Mako said no, it was arguing that while the FCC could give it a new channel without population or coverage protections, it could not deny it that new channel under b(5).

MaKo pointed out to the court that the FCC had all but guaranteed that it would have to squeeze out LPTV's given its spectrum band plan--to clear 126 MHz of spectrum, the most it had envisioned--which will leave the least number of channels left in which to re-pack--FAB's attorney said the term should be "reorganize"--TV stations after the auction.

Judge Sentelle repeatedly asked what LPTV's were secondary to. FAB said it was to full powers and class A's, not conceding that, as applied, LPTV's were secondary to licensed wireless, and certainly not to unlicensed wireless.

Lewis, with an assist from Sentelle, pointed out that the FCC in 2002 had said LPTV's were secondary to licensed wireless, though Sentelle said that was the only example of the FCC saying that he could find, and tweaked Lewis that the FCC in its brief seemed to end its quotations about status before that absence would be apparent.

FAB spent most of its time convincing the court it had standing. It does not own LPTV's but instead options to purchase the stations. The judges seemed to suggest that FAB might fall under the shareholder exemption from being able to bring such a suit, but FAB argued that was a narrow exemption and should not extend to it. Sentelle suggested that was opening the door to shareholder suits.

Lewis said he thought FAB had even less standing than shareholders, who don't have standing to file a similar challenge, and played to Sentelle's and other judges' apparent concern about setting a precedent for shareholder lawsuits. But rather than using the "open door" reference, he likened it to a Pandora's box.

FAB did get to talk about the merits, and argued that Congress could have given the FCC free rein over LPTV's, but didn't, and suggested that despite that the FCC was taking that rein and running with it roughshod over LPTV rights.

Two of the three judges, Sentelle and Srinivasan, are experienced incentive auction repack questioners since they are the same judges to hear last year's broadcaster challenge to how the FCC was protecting, or as broadcasters argued, not protecting TV station market contours in the post-auction repack.

Contributing editor John Eggerton has been an editor and/or writer on media regulation, legislation and policy for over four decades, including covering the FCC, FTC, Congress, the major media trade associations, and the federal courts. In addition to Multichannel News and Broadcasting + Cable, his work has appeared in Radio World, TV Technology, TV Fax, This Week in Consumer Electronics, Variety and the Encyclopedia Britannica.