Book Excerpt: All-Nighter Crisis Just a Legendary Richard Pryor Joke?

Related: An Unforgettable Bond with Johnny Carson’s Son, Rick

On the heels of his highly successful 1982 concert film Live on the Sunset Strip, Richard Pryor, who most top comedians consider the greatest comic of all time and who was a comedy hero of mine, wanted to do another concert film.

This time he wanted to direct it himself and was looking for a TV production team to produce. He wanted to shoot on video and then transfer to film for the theatrical release. He preferred the “more real” look of TV compared to the slicker, more theatrical look of film for his concert films.

Uber entertainment attorney Skip Brittenham, who represented the comedian, thought Richard would be comfortable with my then-production partner Bob Parkinson and me. I think Richard was looking for a new team to go along with his new production company Indigo at Columbia Pictures, which represented a fresh start for Pryor, following a very dark period.

We heard and read the horror stories about working with the mercurial, temperamental star during his well-documented drug using (abusing) years. But after nearly killing himself while free-basing cocaine and going through a long and painful recovery and rehab, he was now sober.

When we met with him at his sprawling estate in the San Fernando Valley, he was calm, low key and charming and even played the drums for us as we spent the afternoon listening to him detail his plans for the movie.

The film was to be called Richard Pryor, Here and Now and it was to be shot over three nights at the recently restored, historic Sanger Theater in New Orleans. But first we would document Richard working out his routines and perfecting the show over several months at the famed Comedy Store in L.A. and a club in Dallas as well.

Any fears we had quickly evaporated and the thrill and absolute joy of being around a true genius in his prime led to one of the greatest experiences of my career.

Except on our first day at the Sanger Theatre, where the final shows would take place, during a sweltering summer week in New Orleans.

We had loaded in our set and equipment with great excitement and were tweaking the huge production trucks when Richard and the great football legend Jim Brown, who also was the project’s executive producer and Richard’s Indigo partner, arrived to do a final prep and tech rehearsal.

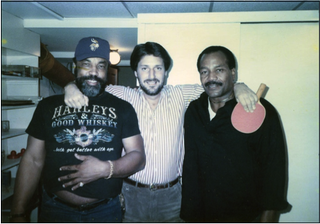

(Pictured left: George Hughley, who ran security for the film, Friendly and Jim Brown playing ping pong at our home.)

Jim was one of my heroes growing up and widely considered the greatest football player of all time.

Richard was in great spirits as he worked with each of the cameramen, explaining his vision as director of the film about how he wanted them to shoot the concerts. He instructed them on when and how to zoom in and out for close ups and wide shots to achieve the best comic and emotional effect. He had a clear vision of what he wanted the film to look like and he communicated it well to his adoring crew. He composed and framed shots and blocked his movements for lighting, camera and sound.

Then he changed into the suit he planned to wear for filming and walked on stage. It was a beautiful, tailored, white silk suit with black pinstripes.

There was one problem: The bright, white silk and pinstripes would not work for video. They created a strobing effect and despite our brilliant crew’s extensive efforts to adjust the lighting, chroma and video levels, nothing could be done to fix it.

The suit, a last minute change, had been purchased by our star the day before to wear all three nights.

He would not accept that he would not be able to wear it.

After an hour of trying to change his mind, the suit became a crisis. Richard was not budging. It was our job to make it work.

We tried everything humanly possible but there was no way to resolve the strobing.

At 10 p.m. our night was just beginning.

We consulted with the best wardrobe people across the country and even one in Paris. Everyone agreed the only possible solution, and an unlikely one, would be to have it dyed to a more muted shade of “crème” or beige which might take some glare off.

We contacted dressmakers, tailors, suit makers, dry cleaners and dye experts to no avail. No one thought we could dye the suit without ruining it.

Several people suggested replacements and offered to open their shops at any hour of the night for Richard to look at alternatives and be fitted.

At midnight we met with Richard, who would have none of it. He was going to wear this suit and that was that. He appeared irritated and for the first time showed hints of the movie star monster we heard and read about.

At one point I made the mistake of half-jokingly saying, “You’re just f***ing with us, right?”

He did not laugh and told me to “get the f**k” out of his suite and that we better fix the problem or he wouldn’t appear the next night.

Jim Brown told us we better get it dyed somehow and make it work.

Finally, a man who had opened his dry cleaning shop for us told us about a woman he knew who had dyed some dresses for a customer years before, using tea bags in a bath tub. He gave us her number.

We would try anything. We woke the poor woman and begged her to give it a try. She warned us that it would almost surely not work, pointed out that it was the middle of the night and asked (rightfully so), “Couldn’t it wait until morning?”

We offered an absurdly high fee and must have made her feel sorry enough for us that ultimately she told us to come over.

So at 2 a.m. in a tiny apartment filled with cats and hanging Mardi Gras beads, a bathtub was filled with hot water and dozens of tea bags and in went Richard’s beautiful new silk suit.

My partner Bob and I thought we may never work again.

At 4 a.m. we were handed the now blueish-beigish, wet, shrunken, severely wrinkled suit and told to let it dry naturally on a hanger and when dry, have it pressed.

Around 9 a.m., our wardrobe person knocked on my door, holding the now dried and pressed--and severely shrunken--suit. She looked alarmed.

Bob and I called Jim to fill him in. Jim took it in stride, thanked us for staying up all night trying and said he’d suggest to Richard that he wear the original dark green suit.

Skip Brittenham said he’d talk to Richard, too.

We were nervous all day and did not hear back about what Richard was going to do until about an hour before the first show was to begin.

Richard’s limo pulled up to the theater with our cameras rolling and the crowds cheering. First out stepped his security guard, George Hughley, followed by Jim, followed by Richard wearing…the original dark green suit.

We breathed for seemingly the first time in 24 hours, but were still scared as hell. Bob and I sheepishly went to greet Richard, not knowing what to expect.

Richard cracked the slightest, wry little smile. In his concert voice he said, “y’all mother***ers done f***ed up my shit” as he held the pathetic, shrunken silk jacket out in his left hand for all to see.

We looked at Jim, we looked at Skip, and they were laughing hysterically and the next three nights went off without a hitch with Richard opening the first night telling the story of the suit and holding it up for the audience to see. Brilliant, hysterical. Pure Richard. (See the moment after the 9 ½ minute mark here.)

To this day, I’m not sure if he was serious or just having some “fun” with us. He never let on he was anything less than serious.

At the premiere, he took Bob and I aside and thanked us for our work in an emotional and sincere way and handed us each a check for $75,000 as a bonus. By far, the most money I’d ever received at one time on top of our generous producing fees.

The film was well-received and shot to number one in its opening weekend. I asked Richard to sign the Variety grosses (see photo left) and it has hung proudly in my study since, along with the poster for the film and a photo of the giant billboard on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood the week it opened (see photo above).

If you haven’t seen his concert films in a while, or ever…you owe it to yourself to do so. The original. The best.

Andy Friendly, the son of CBS television pioneer Fred Friendly, is a producer and former executive. He headed production at King World and primetime programming at CNBC and produced shows such as Entertainment Tonight. This piece is adapted from his forthcoming memoir, Willing to Be Lucky: A Life in TV.

©Andy Friendly

Broadcasting & Cable Newsletter

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below