MBPT Spotlight: The Numbers Game--"Is Our Face Red!" A Big Data Bedtime Story For Researchers With a Happier EndingRed Faces

(Welcome to the first in a new series of Spotlight features, where MBPT asks a top industry research executive to comment on a study or a survey that’s crossed their desk recently. Leading off: Stacey Lynn Schulman of the TVB.)

I don’t know about you, but I get emails almost every day about a new research “study” seeking to either denigrate or indemnify some aspect of our understanding of consumers and the media landscape. Headline-grabbing research is de rigueur these days. The advent of the Internet and social media has birthed a plethora of turnkey research products for inquiring minds to launch a survey and data visualize their results. Expedient? Yes. Cost-efficient? Sometimes. Can you invest in your business around it? Not without careful vetting.

The prevailing opinion among buyers and planners today is that between the volume, velocity and variety of data available to us, we should be able to understand consumers better than they understand themselves—and, therefore, connect with them in ways that surprise and delight. We all want that. But bigger and faster doesn’t mean better. Set-top box data isn’t necessarily better than a sample panel. Yesterday’s behavior will not always predict tomorrow’s.

Market researchers know that conducting research that has a sound theoretical basis and an explicit set of assumptions is the requirement of any research that seeks to project its findings to a population with a known degree of accuracy. This is the foundation of Probability Sampling. I guarantee you that a great deal of the industry research you see touted in the press to promote one medium or service over another does not meet these guidelines. So how do you know which studies meet the sniff test?

Recently, the American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) released a 126-page white paper on Non-Probability Sampling (meaning, all those research methods that yield results that aren’t necessarily representative or projectable). Arguably, it’s not written for the average media or marketing executive, but even if you read through the 5-page Executive Summary, you can learn a lot. Here’s why I think it’s an important read for media and marketing executives:

• You’re tired of hearing your research director tell you not to use a piece of insight because it’s “not representative.”

• You’re still trying to figure out how Nielsen can project TV ratings for the entire United States from 12,000 (give or take) homes.

Broadcasting & Cable Newsletter

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

• You’re a big believer in Big Data and need to find a research approach to using it in your organization that makes it not only cool, but respectable.

Truth be told, reason No. 3 is perhaps one of the most important reasons to dig into this study and upgrade your research IQ. The AAPOR Task Force does a fine job of defining a variety of statistical methods that have been employed in the last several years to mitigate bias in non-probability samples so that results become more meaningful and even projectable. These methods will become more important in the near future as more and more sets of Big Data (and various vendors) are employed by marketers, agencies and media companies to better understand consumer behavior.

Only Thing We Have to Fear Is Incorrectly Sampled Data

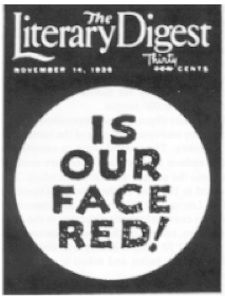

Still not intrigued? Consider this headline-grabbing research poll reported in the Literary Digest regarding the 1936 Presidential election:

Landon, 1,293,669; Roosevelt, 972,897

“Landon in a landslide,” as we all know, never came to be. The fascinating point about this moment in history is that the sheer size of the research study was more prominent than the findings themselves.

The magazine, which had successfully predicted presidential victors throughout the 1920's and early ‘30s, endeavored to launch the mother of all public opinion polls—reaching out to 10 million voters in its Titanic-sized quest for irrefutability. The results, culled from 2.2 million actual responses (an astronomical count that far outpaced any other research study of its time) predicted Landon would win in a landslide, taking 57.1% of the popular vote and an Electoral College margin of 370 to 161.

At the same time, a young pollster named George Gallup conducted his own survey of 50,000 Americans and concluded that Roosevelt would prevail. In the end, Roosevelt took 60.8% of the popular vote, along with a spectacularly dominant 523 to 8 Electoral College victory (the largest of any presidential election).

Literary Digest, in a tongue-in-cheek attempt at humility, ran a cover page with the words “Is Our Face Red!” in the week following the election. The Digest published its last issue in 1938—fascinatingly enough, its presidential prediction has now historically been identified as the reason for its demise.

Gallup, on the other hand—much like the four-term president whose victory he predicted—went on to build his public opinion polling business, gaining credibility with his election research.

The Literary Digest case study is often used in statistical research courses to exemplify the dangers of various forms of bias in research sampling. Academics have argued about whether the Digest study suffered more from self-selection bias (the magazine drew its sample from subscribers and telephone and automobile owners—all hallmarks of wealthy citizens in those times, thereby missing the sentiment of the poorer ranks of voting society) or from non-response bias (they invited 10 million to participate and only 20% responded). Either way, despite the enormity of the data set, the conclusions were inaccurate due to a flawed research design. Big, in this case, was not better.

Finding the Right Way In

That said, the AAPOR white paper does provide an informed opinion on techniques being employed today to improve the reliability and predictability of research using non-probability samples from online surveys to Big Data. No one technique can ameliorate all research issues, but it’s an important first step toward recognizing and validating the need for new approaches for a new world. Even the AAPOR researchers recognize that probability sampling isn’t the only approach to understanding, invoking a quote from one of the most famous American statisticians, Leslie Kish (1965): “Great advances of the most successful sciences—astronomy, physics, chemistry—were and are achieved without probability sampling.”

From this researcher’s perspective, we are standing on the precipice of a new world order. Quality research techniques are still fueling our media and marketing decisions but, admittedly, they are as challenged by our complex world as we are in navigating our TV program guides. New data sets are becoming an unavoidable reality, necessitating more unorthodox techniques that frankly need to be evaluated for scientific merit. The AAPOR paper, and others like it (the Media Rating Council has also written a white paper on the same topic) are important attempts to validate and illuminate our way forward.

For more information on the AAPOR’s paper on Non-Probability Sampling, click HERE.

To learn more about the Literary Digest case study, the University of Pennsylvania provides a short explanatory article HERE.

To read the Media Rating Council paper on "On Probability Sampling, Babies and Bathwater," click HERE.