Sinclair's SpreeDazzles Street,Puzzles Stations

There’s been nothing short of a flood of TV station acquisitions over the past few years, and if there’s a common denominator among them, it’s that Sinclair Broadcast Group did the buying— or came close to doing so. The burgeoning Baltimore broadcaster, easily the most controversial station group around, agreed in April to pay $373.3 million in its latest acquisition, the 20- station Fisher Communications group, bringing its station acquisitions bill to around $2 billion in the past 20 months. If an owner is looking to unload a batch of TV stations small or large, Sinclair is probably the first place to start.

“I think every broker has Sinclair on speed dial,” said Larry Patrick, founder of Patrick Communications.

David Smith, chairman, president and CEO of Sinclair, has made it crystal clear that he hopes to continue his spending spree. Speaking with investors after the Fisher acquisition, Smith said the company could double in size and still find room under the FCC’s ownership cap. This ensures that Sinclair will continue to dominate discussions about local broadcasting for the foreseeable future, with the most popular topics being whether the group can manage its increased debt load, what is motivating the station group grabs, and what it all means for broadcasting—and the public it serves.

“Sinclair has a lot of dry powder,” said Patrick. “They can probably go out and buy a billion dollars’ worth of stations, if not more.”

Sinclair on a Tear

Working out of a nondescript office building in suburban Baltimore, the Sinclair brain trust rarely addresses the media, and its station general managers typically do not speak to reporters either. David Smith did not return calls for comment. Such public reticence enhances the air of mystery around the group—and its intentions.

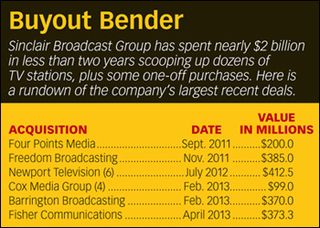

Sinclair’s emergence from a collection of alsoran Fox, CW and MyNetworkTV affiliates in recent years to a group possessing several market leaders and covering close to 34% of U.S. households has been historic—not to mention nothing short of stunning. The run kicked off with a $200 million buy of the Four Points group in September 2011, then $385 million for the Freedom Broadcasting stations that November, followed by $412.5 million for six Newport TV stations, $99 million for a Cox quartet and a $370 million Barrington Broadcasting pickup, the latter slated for Sinclair’s new Chesapeake TV subsidiary. Sinclair has also acquired single stations, and agreed to acquire the Fisher stations in April.

Sinclair’s almost $2 billion in M&A represents nearly half of the $4.1 billion total spent on TV station acquisitions since September 2011, according to BIA/Kelsey. And the company isn’t likely finished. As Smith told investors in his post-Fisher address, Sinclair benefits from the way the FCC counts a UHF station for half of its market reach against the ownership cap. “We’re at 18%-20%, the way the FCC calculates the number,” he said. “We can double, theoretically, in size and still not be at the 39% number.”

Rocking the Retrans

The buying flurry has industry watchers wondering whether all the action represents a spectrum grab in advance of the incentive auction; whether David Smith has, in the words of one member of his inner circle, “found religion” in terms of local news’ power to serve the public good; or whether it’s strictly revenue-driven.

Retransmission consent is a huge part of the equation. Due to its hardball negotiations in the past with cable, satellite and telco operators, Sinclair is enjoying a retrans windfall with each acquisition that is alternately known as the after-acquired clause or “favored nation” status. In simple terms, newly acquired stations are grandfathered into the same retrans rate as Sinclair’s existing stations, typically a significant jump that spells major pro"ts when multiplied across scores of subscribers.

One insider with knowledge of the deals explains how a small broadcaster getting 40 cents per subscriber per month sells its stations to Sinclair, whose stations get a dollar. Suddenly, the acquired stations are on for a buck a sub too. “The moment they close the deal, it jumps an extra 60 cents,” said the insider. “If you have a million households, that’s $600,000 a month. Even if you give half of that to the network, it’s $3.6 million more [per year] in cash flow.”

Such favorable arbitrage is a major motivation to get bigger. “It’s put them in a position where many assets in the marketplace are worth more in Sinclair’s hands than if they’re independently held,” said David Bank, managing director of equity research at RBC Capital Markets.

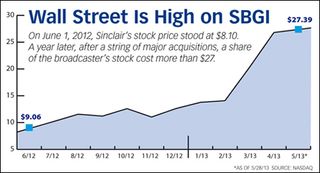

Wall Street has vociferously applauded Sinclair’s growth plans. In September 2011, Sinclair’s stock price hovered around $7. A year later, it climbed to over $12. These days, it’s over $27 and may not be done climbing. Following the announcement of the Fisher acquisition, Wells Fargo Securities raised Sinclair’s price range from $24- $26 to $32-$34. “Perhaps the biggest positive takeaway outside the numbers is that there is still plenty more SBGI could do,” wrote Marci Ryvicker, Wells Fargo senior analyst.

Does News Lose?

Those in TV news are not as ebullient as Wall Street. Industry watchers are curious about how much of Sinclair’s enriched windfall goes back into its local properties. The viewpoint from the station level is, for the most part, favorable. In Grand Rapids, Mich., where Sinclair acquired WWMT in the Freedom deal, the spending on news is evident in a pair of LiveU video transmission packs and the new weekend-morning newscasts that Jim Lutton, VP and general manager, said he had tried to get off the ground for three years under the previous owner. “They’ve been very good about giving us a lot of support for news product,” Lutton said of Sinclair.

Sinclair stations are not traditionally known as news powers, but the group appears interested in elevating its game. Among recent acquisitions are market leaders WKRC Cincinnati and WHAM Rochester (N.Y.). A year ago, Scott Livingston, news director at Sinclair flagship WBFF Baltimore, was elevated to a group VP role. “His years of experience overseeing highly successful newscasts are invaluable, especially when you consider the size of our news franchise he will be leading,” Smith said at the time.

More recently, Bill Anderson, former news director at WTVR Richmond, was named director of news standards and practices for the group. Both are new positions at Sinclair, and the moves may help assuage anxious public interest groups.

“I think it’s fair to say a number of people in the industry have some concerns about Sinclair because of the history of their relationship with local news,” said Bob Papper, author of the annual RTDNA-Hofstra University TV station surveys and distinguished emeritus professor of journalism at Hofstra. Papper notes Sinclair’s shuttering of newsrooms in some markets and its controversial centralized news content out of Baltimore in years past. But he also said Sinclair’s commitment to news appears to have revived. “I think what you have now in the industry is a wait and see,” Papper said.

Sinclair got in hot water for airing specials that, to many, trumpeted an ultra-conservative agenda, including one that ran on the eve of the 2012 elections in swing states. Many are curious if the company will use its expanded platform to broadcast its ideology—or keep things down the middle. “I give them credit— they recognize there’s a market in news and a value in news,” said a veteran TV news exec. “It’s not their job to dictate the agenda, but to let the market dictate the agenda.”

Sinclair’s growth has also caused ripples in the syndication world. With Sinclair currently remaining outside the Top 20 markets, the likes of Tribune and the networks’ owned station groups continue to be the ones that make or break syndicated show programming. But Sinclair is king among the next tier of markets, say syndication veterans. One who asked not to be named due to a business relationship with Sinclair said getting the group on board with a show is key to getting large swaths of the country covered.

“If you want clearances in the elusive 80%- 85%-90% range, it’s got to include Sinclair, or you have to go back and figure out how to piece it together,” said the syndication veteran. “If you’re looking past the top markets, you’ve got to go to Baltimore to make your case.”

D.C. Drama

Another source of controversy surrounding Sinclair is what some see as a lax regulatory environment that has enabled the group to grow at such a rapid clip. Many believe Sinclair derives ownership benefits from closely aligned companies, such as Cunningham Broadcasting, that it does not technically own. Others say the FCC’s UHF discount is woefully out of date.

Alan Frank, who retired from the president/CEO post at Post-Newsweek at the end of the year, said he repeatedly heard the term “bad actor” from the FCC and Congress in his countless trips to Capitol Hill as an industry leader—as in, the rules and regulations are there to protect the honest broadcasters from the bad actors who might exploit the law, according to regulatory executives. Frank senses some hypocrisy on the Hill. “The way Sinclair operates is so far removed from the spirit of what the laws are. It’s astonishing to me that the FCC and Congress elect to turn a blind eye to it,” he said. “In markets where there are five stations, they own three. How is that anything but being a bad actor? It’s a sham— and a shame.”

Others counter that Sinclair is merely pushing the envelope—legally—to grow its business. One broadcast attorney who requested anonymity said he had not looked at Sinclair’s paperwork, but noted that the group’s acquisitions and service agreements continue to pass regulatory muster. “I get the sense Sinclair is pushing it right up to the line, if not over it, but the FCC keeps approving them,” the lawyer said. “It may not be how the other [station groups] operate, but if the FCC OKs it, who’s to say it’s wrong?”

Larry Patrick agreed. “A lot of people complain, but they’re not legally doing anything wrong,” Patrick said. “I think some of it may be jealousy.”

Frank isn’t having it. “Congress and the FCC are supposed to be public servants,” he said. “They look us in the eye and say we’re all about catching bad actors. You really expect us to look at you with a straight face when you say that? I find it duplicitous at best.”

An FCC representative declined to comment, citing agency policy.

An Acquired Taste

While the FCC will soon be getting a new chairman, several sources agree that things are unlikely to change much on the regulatory front. That means Sinclair will have a green light to continue expanding its massive footprint; the likes of Titan Broadcast, Grant Broadcasting and others may end up in the portfolio. After all, growing your reach only makes it easier to, well, grow your reach.

“The bigger you are, the more leverage you have in terms of content [and] carriage,” said RBC Capital’s Bank. “And as you get more leverage, that in turn helps you get bigger still. I think Sinclair is in a very good place in this virtuous cycle. They have certainly put themselves in a very strong position.”

E-mail comments to mmalone@nbmedia.com and follow him on Twitter: @BCMikeMalone

Broadcasting & Cable Newsletter

The smarter way to stay on top of broadcasting and cable industry. Sign up below

Michael Malone, senior content producer at B+C/Multichannel News, covers network programming, including entertainment, news and sports on broadcast, cable and streaming; and local broadcast television. He hosts the podcasts Busted Pilot, about what’s new in television, and Series Business, a chat with the creator of a new program, and writes the column “The Watchman.” He joined B+C in 2005. His journalism has also appeared in The New York Times, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Playboy and New York magazine.